For English language please see below Sehen Auf See

Essay von Dr. Rolf Sachsse Bevor der Mensch in See stach, konnte er aufrecht gehen; seither ist ihm der Horizont Garant von Richtung und Ankunft. Das Resultat ist eine visuelle Vorstellungswelt, die seit dem späten 18. Jahrhundert panoramatisch, d.h. ganzräumlich, genannt wird: Horizontal unkritisch lässt sich ein jeder Blick nach rechts und links erweitern, bis zum Rundum-Sehen und darüber hinaus. In der Horizontalen erkennen wir Menschen vor allem Helligkeitsunterschiede, weiche Verläufe und Abschattierungen. Vertikal dagegen richtet sich für den Menschen alles Wesentliche aus, wird der kritische Unterschied zwischen Farbtönen und Umrisslinien von Tieren oder Pflanzen gemacht, der im Stolpern, Fliehen, Jagen und Transportieren überlebensnotwendig ist. Für die Seefahrt haben sich derlei frühmenschliche Bedingungen selbstverständlich erhalten: Die Kunst des Segelns ist eine vertikale Beschäftigung höchster Konzentration, und die wichtigsten Gerätschaften zur Orientierung auf See werden nach Höhenwinkeln ausgerichtet. Für das Bildermachen gilt – spätestens mit dem Höhlengleichnis Platos – genau das Gleiche: Die Schatten können horizontal bis in die unendliche Tiefe des Raumes reichen, bedeutend sind allein die Geschehnisse zwischen Mensch und Schatten, hier und jetzt, auf kurze Distanz, vertikal.

Der Fotograf Herbert Böttcher verweist gern darauf, dass die panoramatische Sicht seiner Kamera dem natürlichen Sehen entspräche – und doch sind es Bilder, die er hier präsentiert, Artefakte von hoher Präzision und ausgefeilter Machart. Und sie sind exakt so organisiert, wie es die Bedingungen des Sehens auf See und zu Land erfordern: im Vordergrund, am unteren Bildrand präzise und scharf, auf wie über dem Horizont eher weich und unbestimmt. Das erste Ergebnis , die erste Sicht aufs Bild ist daher eine Irritation: Über dem Horizont scheint die Perspektive eine andere zu sein als darunter. Wo am unteren Bildrand die Container, Ladeflächen, Luke, Gangways, der Bug, das Heck und viele andere Details in starken Fluchten zur Seite streben und den Eindruck eines Sogs in die Tiefe erwecken, reihen sich am Wolkenhimmel die Elemente scheinbar ruhig nebeneinander, streben nur wenig auseinander. Wer genau hinsieht, bemerkt die Differenz der Schärfen und Unschärfen: Viele der Wolken haben Doppelkonturen, genau in der Distanz des Wellenhubs und seiner Abbildung in der Fotografie. Wer einige Male auf Schiffen fuhr, kennt diesen Effekt vom Sehen mit bloßem Auge bei Dämmerlicht, und einige Marinemaler des 18. Jahrhunderts haben die gleiche Verdopplung zur Steigerung der Dramatik eingesetzt.

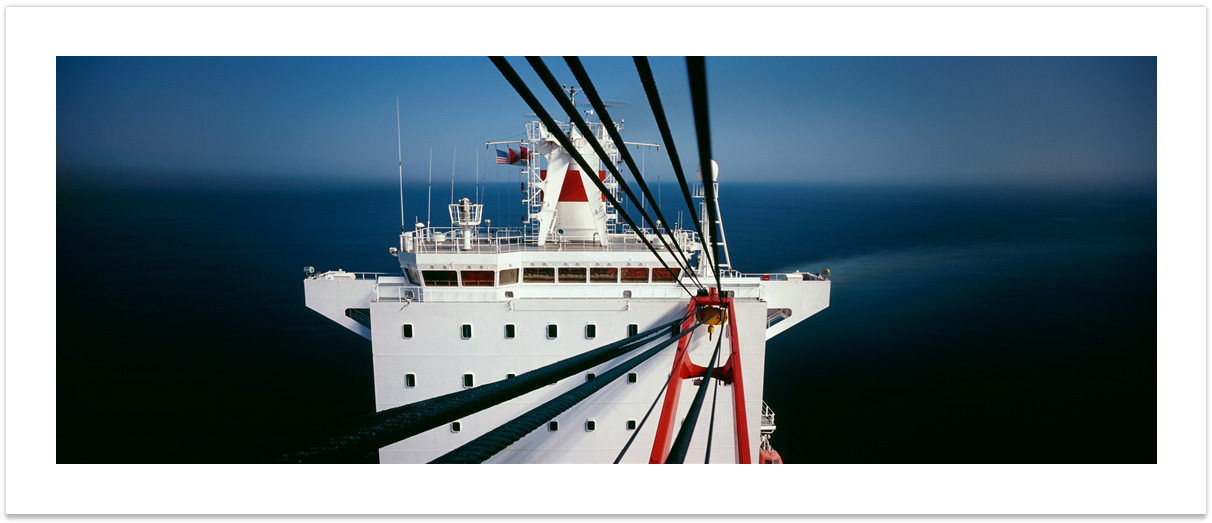

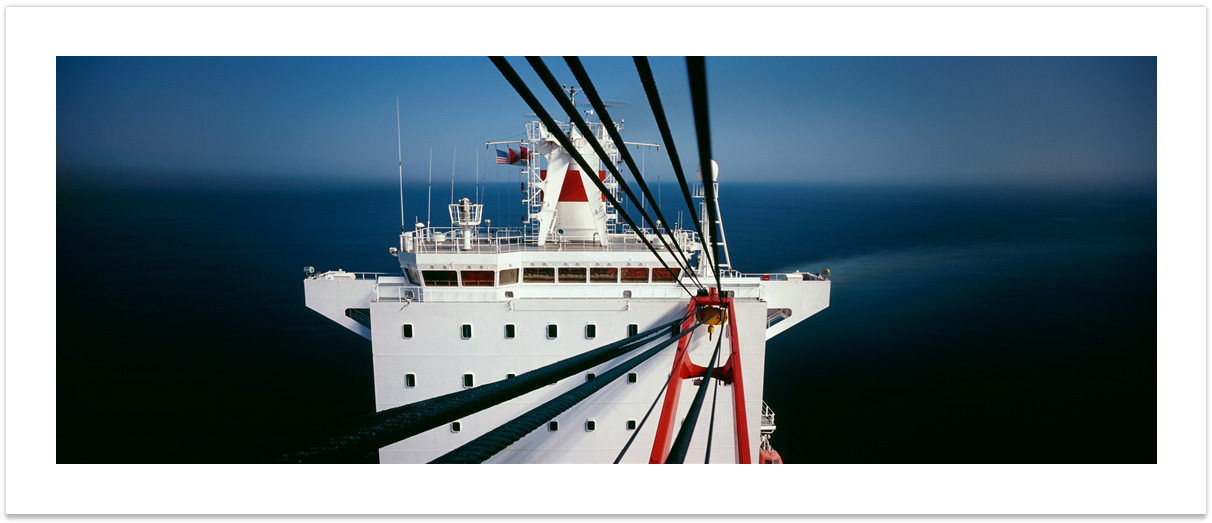

Doch Herbert Böttcher fotografiert seine Bilder, und ein großer Unterschied zur Malerei wird hier in den Farben repräsentiert: Containerschiffe haben weiße Brücken und rote Decks, die Container selbst strahlen in den Standardfarben der Metallnormlackierungen, meist rot, blau oder weiß, und dienen obendrein als Werbefläche, mit Logos, Typographie und Hinweisen in allen Handelssprachen dieser Welt. Bei den Farben des Himmels und des Wassers kann er sich auf die Eigenarten seiner Filme verlassen, die kurzwelliges Licht überproportional stark registrieren. Das Resultat ist ein durchgängiger Farbdreiklang aus blau, rot und weiß – nicht umsonst die Farben der Seefahrt. Besonders klar erscheint dieser Farb-Akkord bei einem der Kernbilder des Buchs: die weiße Brücke mit den schwarzen Tauen und roten Kranteilen vor tiefblauer See. Wird das Gelb des künstlichen Lichts in der Nacht hinzu genommen, ist man beim modernen Farbklang der konstruktivistischen Künstler vom Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts, bei Theo van Doesburg und Piet Mondriaan, aber auch beim Wassily Kandinsky des Bauhauses. Diese Künstler hatten das Grün – und alle Erdfarben ohnehin – von ihrer Palette verbannt, weil es dem technischen Zeitalter nicht mehr entsprach. Noch vor dem Flugzeug war der Ozeandampfer zur Ultima ratio moderner Konstruktivität geworden, und da bedurfte es keiner Erdenhaftung mehr. Wenn Herbert Böttcher denselben Farb-Akkord in seinen Seestücken verwendet, dient es eher als Hinweis darauf, dass die Reederei ein letzter Hort der Schwerindustrie ist, für deren Transporte sie allein sorgen kann. Zudem stellt der Farbklang die Bildnerei des Fotografen unbedingt in einen Zusammenhang der Moderne, heute aber eher als Zitat denn in naivem Fortschrittsglauben.

In den Salons des 18. und frühen 19. Jahrhunderts gehörten Marinebilder zu den teuersten Stücken, und das nicht nur, weil die Sammler mit viel Kaufkraft ausgestattet waren: Die Qualität eines Seestücks bemaß sich im Vergleich der Dramatik – oder Ruhe –einer Szenerie vor allem daran, dass sowohl die schiffstechnischen als auch die metereologischen Details stimmten, und dafür musste der Maler sein Handwerk genauso verstehen wie die Freuden und Nöte der Schifffahrt. Immer schwang in diesen Bildern ein Hauch von dem mit, was leichthin mit dem Begriff der Romantik verbunden wird, eine Selbstgenügsamkeit im Anspruch des Machens und der erhofften Meditation beim Betrachten. Manche Bilder dieses Buchs weisen in diese Richtung. Es sind typischerweise genau jene, bei denen die gestalterischen Mittel eingeschränkt werden: nahezu monochrome Ansichten unscharfer Wellen mit Leuchtspuren anderer Schiffe oder Bojen. Im Kontext des vorliegenden Bildessays haben sie eine feste Aufgabe: Sie deuten umso stärker auf die Modernität des Geschehens insgesamt hin. Und sie sind notwendiges Pendant zu einem anderen Genre, das die Marinemalerei erst im 20. Jahrhundert, auf der Grundlage der Fotografie, finden konnte: das Nachtbild mit künstlichem Licht und streifenförmigen wie stroboskopischen Bewegungslinien. Hier präsentiert sich Herbert Böttchers Fotografie als radikal modern, als echte Nachfolgerin jener hoffnungsfrohen Ansichten amerikanischer Großstädte aus den 1920er Jahren, die Architekten wie Erich Mendelsohn und Knud Lönberg-Holm in die Fotografie einführten und die der Multimedia-Künstler László Moholy-Nagy 1938 um jene Farbigkeit erweiterte, die auch Herbert Böttcher verwendet. Mit Nachtbildern erwiderten diese Künstler jener anderen Kunst ihre Referenz, die als nächtliche selbst unbedingt modern war: dem Film und ihrem Schauplatz, dem Kino.

An das Kino mögen manche Bilder von Herbert Böttcher erinnern, und das aus gutem Grund. Es sind Kino-Geschichten, die hier erzählt werden, Bilder vom Fahren und Laden, vom Reisen und Anhalten, vom Kommen und Gehen. Doch das Medium dieses Buchs ist die Fotografie, und sie vermittelt einen radikalen Schnitt in die Zeit – soweit die gängige Theorie seit Walter Benjamin und Roland Barthes. Herbert Boettcher gehört zu jenen Fotografen, die eine solche, technische Begrenzung nie als unumstößlich akzeptiert haben: Mit Vilém Flusser spielt er gern gegen den Apparat, oder besser noch: Er konterkariert die Moderne, indem er ihre Mittel bis zum letzten Ende ausschöpft. Zwei Zeitebenen finden sich in allen seinen Bildern: die lange Verschlusszeit bei der Herstellung des Bildes und die kurze Zeit präziser Objektregistrierung im menschlichen Auge. Ihre Differenz ist die eigentliche Regel seines Arbeitens. Bei der nächtlichen Hafenein- oder ausfahrt wird der Schiffskörper samt Ladung bis zur kleinsten Schraube des letzten Containers überaus präzise und exakt widergegeben, wie bei einer Momentaufnahme im Sport oder einer Studioproduktion für Industrieprodukte. Demgegenüber markieren Lampen und Leuchten am Horizont oder in der Umgebung der Aufnahme lange Spuren an Himmel und Wasseroberfläche, oft bis zur Bildung eines textilen Streifenmusters, immer aber in strikter Zentralperspektive mit exakt definiertem Fluchtpunkt auf dem Horizont. Es ist ein Effekt, den sich im Film die Animationsstudios zunutze machen, indem sie ober- und unterhalb des Horizonts verschiedene Geschwindigkeiten des Bildgeschehens konstruieren; hier sind die Differenzen in ein Bild eingefroren, und das Kino findet im Kopf statt.

Für die Bilder dieser Serie verwendet Herbert Böttcher eine Breitbildkamera, deren Optik auf das extreme Seitenverhältnis von eins zu drei berechnet ist und die daher alle Details bis in die Ecken des Bildfelds hinein mit minimalem Winkelfehler und geringem Lichtabfall aufzeichnet. Auch dieses Instrument – nicht umsonst werden nautische und fotografische Apparate mit Erzeugern mechanischer Musik gleich benannt – ist für die Malerei lange eingeführt, als Camera Obscura die Grundlage einer perspektivisch exakten, für architektonische wie technische Sujets gleichermaßen Vedutenmalerei. Alles Technische auf und an den Schiffen ist in höchster Präzision widergegeben, ohne Verzerrung und bis ins kleinste Detail hinein dechiffrierbar. Der Kontrast zum weichen Wasser mit seinen scheinbar flachen Wellen und zum Himmel ohne Begrenzung könnte kaum größer sein: Mehr Vertrauen in die Machbarkeit von Container-Transporten kann nicht vermittelt werden. Fotografische Technik und Sujets der Bilder verschmelzen hier in einer Weise, wie sie zuletzt noch für die Abbildung industrieller Großanlagen galt. Es ist eine weithin unbekannte, dennoch real vorhandene Welt, die auf diesen Bildern vorgeführt wird.

Die Bilder von Herbert Böttcher existieren auf zweierlei Weise, zum einen als Seiten dieses Buchs und zum anderen als Einzelstücke an der Wand. Der Unterschied ist bedeutend. Für die Präsentation als Einzelstück hat der Künstler mit dem Diasec-Verfahren eine Form gefunden, die dem Eindruck von Himmel und Wasser auf den Fotografien sehr nahe kommt – die spiegelnde Oberfläche der Acrylglas-Kaschierung dieses Positiv-Verfahrens sorgt für eine ähnliche Tiefe im räumlichen Eindruck wie die verwischten Konturen der Bugwellen und Heckschäume, wirkt im gleichen Moment jedoch auch so technisch präzise wie die Schiffsaufbauten im Bild. Im Buch ist das einzelne Bild weniger wichtig, sondern wird beim gleichmäßigen Blättern – das sich alle Büchermacher als Ideal vorstellen – zum Teil eines Rhythmus der Betrachtung, unabhängig von der Blätterrichtung und vom Anfangsbild. Ein Bildessay ist nach völlig anderen Gesichtspunkten aufgebaut als ein in Buchstaben geschriebener, für den wir uns immer noch das Lesen von vorn nach hinten nicht abgewöhnt haben. Im Bildessay wechseln Perspektivfluchten einander ab – mittig, nach links fluchtend, von oben nach unten –, genauso wie diverse Farbstellungen oder die Nacht-, Dämmerungs- und Tagbilder. Dem Unterschied von bewegtem Wasser und ziehenden Himmel zu den technischen Aufbauten in jedem Bild gemäß folgen auch die Rhythmen im Buch hintergründigen Regeln von Abfolgen, wie sie jede musikalische Komposition auszeichnen. Doch die Betrachter können selbst entscheiden, wessen Rhythmus sie erkennen möchten: das Kopfmotiv von Tschaikowsky, die Passage von Mussorgsky, den Sonnenaufgang von Sibelius und die Nachtmotive als Boogie oder Bebop – oder ganz etwas anderes.

Um zu den anthropolgischen Bestimmungen des Anfangs zurückzukehren: Der Mensch musste sich mit Werkzeug ausstatten, um in der ihn umgebenden Natur zu überleben, und er brauchte Kenntnisse aller Art, um sich in der ganzen Welt bewegen zu können. Wie die nautischen Instrumente ist die Kamera eine Bewehrung des Auges, um sich wie anderen beweisen zu können, dass man sich die Welt untertan machen kann, und sei es als Bild. Die Begrenztheit dieses Tuns ist inzwischen jedem Menschen auf dieser Welt bewusst – und genau da setzt die Romantik der Bilder von Herbert Böttcher an. Indem sie ein letztes Mal große Triumphe der Technik feiern, diese aber durch kleine Brüche in jedem einzelnen Bild wie in der Abfolge dieses Buches sichtbar werden lassen, führen sie alle, die sowohl noch über die stupende Qualität staunen können als auch sich der Mühe genaueren Betrachtens unterziehen, genau da hin, wo jede gute Romantik führt: an das Verständnis der Eingebundenheit menschlichen Wirkens in die Kräfte der Natur. Auch davon wird in diesen Bildern viel gezeigt, und das kann jeder Betrachter für sich selbst in ihnen finden, jenseits aller Sprache.

Rolf Sachsse

Der Essay von Dr. Rolf Sachsse erschien 2008 im Bildband Seamotion.

EN

Seeing At Sea

Seeing At SeaEssay by Dr. Rolf Sachsse

Before man set sail, he could walk upright; since then, the horizon is his guarantee of direction and arrival. The result is a visual world of imagination, which since the late 18th century is called panoramic, i.e. entire space: Horizontally uncritical, any gaze can be extended to the right and left, to all-round vision and beyond. In the horizontal we humans recognize above all brightness differences, soft gradients and shadings. Vertically, on the other hand, everything essential aligns for humans, the critical difference is made between color tones and outlines of animals or plants, which is necessary for survival in stumbling, fleeing, hunting and transporting. For seafaring, such early human conditions have been preserved as a matter of course: The art of sailing is a vertical occupation of highest concentration, and the most important tools for orientation at sea are aligned according to altitude angles. For picture making – at the latest with Plato’s cave allegory – exactly the same applies: Shadows can reach horizontally into the infinite depth of space; what is significant is solely what happens between man and shadow, here and now, at a short distance, vertically.

Photographer Herbert Böttcher likes to point out that his camera’s panoramic view corresponds to natural seeing – and yet the images he presents here are artifacts of high precision and sophisticated making. And they are organized exactly as required by the conditions of seeing at sea and on land: precise and sharp in the foreground and at the lower edge of the image, rather soft and indeterminate on and above the horizon. The first result, the first view of the picture is therefore an irritation: above the horizon, the perspective seems to be different than below it. Whereas at the lower edge of the picture the containers, loading areas, hatches, gangways, the bow, the stern, and many other details move sideways in strong alignments and give the impression of a pull into the depths, in the cloudy sky the elements seem to line up calmly next to each other, moving only slightly apart. If you look closely, you will notice the difference between the sharpnesses and blurs: Many of the clouds have double contours, exactly at the distance of the wave stroke and its image in photography. Anyone who has sailed on ships a few times knows this effect from seeing with the naked eye in twilight, and some 18th-century marine painters used the same doubling to heighten the drama.

But Herbert Böttcher photographs his images, and a major difference from painting is represented here in the colors: Container ships have white bridges and red decks, while the containers themselves shine in the standard colors of metal paint, usually red, blue, or white, and serve as advertising space to boot, with logos, typography, and notices in all the world’s commercial languages. For the colors of the sky and water, he can rely on the peculiarities of his films, which register short-wave light disproportionately strongly. The result is a continuous color triad of blue, red and white – not for nothing the colors of seafaring. This color chord appears particularly clearly in one of the core images of the book: the white bridge with the black ropes and red crane parts in front of a deep blue sea. If the yellow of the artificial light in the night is added, one is at the modern color chord of the constructivist artists of the beginning of the 20th century, at Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondriaan, but also at Wassily Kandinsky of the Bauhaus. These artists had banned green – and all earth colors anyway – from their palette because it no longer corresponded to the technical age. Even before the airplane, the ocean liner had become the ultima ratio of modern constructiveness, and there was no longer any need for earthiness. When Herbert Böttcher uses the same color chord in his sea pieces, it rather serves as an indication that the shipping company is a last refuge of heavy industry, for whose transports it alone can provide. Moreover, the color chord necessarily places the photographer’s imagery in a context of modernity, but today more as a quotation than in naive faith in progress.

In the salons of the 18th and early 19th centuries, marine paintings were among the most expensive pieces, and not only because collectors were endowed with a lot of purchasing power: The quality of a marine piece, when compared to the drama – or tranquility – of a scene, was measured primarily by getting both the naval and the metereological details right, and for that to happen, the painter had to understand his craft as well as the joys and hardships of navigation. Always resonating in these paintings was a touch of what is easily associated with the term Romanticism, a self-sufficiency in the aspiration of making and the hoped-for meditation in viewing. Some of the images in this book point in this direction. They are typically precisely those in which the creative means are limited: almost monochrome views of blurred waves with tracers of other ships or buoys. In the context of the present picture essay, they have a fixed task: they point all the more strongly to the modernity of the event as a whole. And they are a necessary counterpart to another genre that marine painting was only able to find in the 20th century, on the basis of photography: the night image with artificial light and streaky as well as stroboscopic lines of movement. Here Herbert Böttcher’s photography presents itself as radically modern, as a true successor to those hopeful views of American cities from the 1920s, which architects such as Erich Mendelsohn and Knud Lönberg-Holm introduced to photography and which the multimedia artist László Moholy-Nagy expanded in 1938 to include the kind of colorfulness that Herbert Böttcher also uses. With night pictures these artists returned their reference to that other art, which as nocturnal itself was necessarily modern: the film and its setting, the cinema.

Some of Herbert Böttcher’s pictures may remind you of the cinema, and for good reason. They are cinema stories told here, pictures of driving and loading, of traveling and stopping, of coming and going. But the medium of this book is photography, and it conveys a radical cut into time – as far as the common theory since Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes goes. Herbert Boettcher is one of those photographers who have never accepted such a technical limitation as irrevocable: With Vilém Flusser he likes to play against the apparatus, or even better: he counteracts modernity by exhausting its means to the last end. Two temporal planes can be found in all his pictures: the long shutter speed in the production of the image and the short time of precise object registration in the human eye. Their difference is the very rule of his work. When a ship enters or leaves a harbor at night, the hull of the ship, including its cargo, is reproduced with extreme precision and accuracy, down to the smallest screw of the last container, as in a snapshot in sports or a studio production for industrial products. In contrast, lamps and lights on the horizon or in the vicinity of the shot mark long traces on the sky and water surface, often to the point of forming a textile stripe pattern, but always in strict central perspective with a precisely defined vanishing point on the horizon. It is an effect that animation studios exploit in film by constructing different speeds of the pictorial action above and below the horizon; here the differences are frozen into one image, and the cinema takes place in the mind.

For the images in this series, Herbert Böttcher uses a widescreen camera whose optics are calculated for the extreme aspect ratio of one to three and which therefore records all details right into the corners of the image field with minimal angular error and light fall-off. This instrument, too – not for nothing are nautical and photographic apparatuses named the same as producers of mechanical music – has long been introduced for painting, as camera obscura the basis of a perspective-exact, for architectural as well as technical subjects equally veduta painting. Everything technical on and around the ships is reproduced with the highest precision, without distortion and decipherable down to the smallest detail. The contrast to the soft water with its seemingly flat waves and the sky without boundaries could hardly be greater: More confidence in the feasibility of container transport cannot be conveyed. Photographic technique and the subjects of the images merge here in a way that was last seen in the depiction of large-scale industrial plants. It is a widely unknown, yet real world that is presented in these pictures.

The pictures of Herbert Böttcher exist in two ways, on the one hand as pages of this book and on the other hand as single pieces on the wall. The difference is significant. For the presentation as individual pieces, the artist has found a form in the Diasec process that comes very close to the impression of sky and water in the photographs – the reflective surface of the acrylic glass lamination of this positive process provides a similar depth in the spatial impression as the blurred contours of the bow waves and stern foams, but at the same moment also appears as technically precise as the ship superstructures in the picture. In the book, the individual image is less important, but becomes part of a rhythm of contemplation when the pages are turned evenly – which all bookmakers imagine to be the ideal – regardless of the direction of the page or the initial image. A picture essay is structured according to completely different points of view than one written in letters, for which we still haven’t gotten out of the habit of reading from front to back. In the picture essay, perspective flights alternate with each other – centered, aligned to the left, from top to bottom – just like various color settings or the night, twilight and day images. In accordance with the difference between moving water and drifting sky and the technical structures in each picture, the rhythms in the book also follow enigmatic rules of sequences, as they characterize every musical composition. But viewers can decide for themselves whose rhythm they want to recognize: the head motif by Tchaikovsky, the passage by Mussorgsky, the sunrise by Sibelius, and the night motifs as boogie or bebop – or something else entirely.

To return to the anthropolgical provisions of the beginning: Man had to equip himself with tools to survive in the surrounding nature, and he needed knowledge of all kinds to be able to move in the whole world. Like the nautical instruments, the camera is a reinforcement of the eye to be able to prove to oneself as well as to others that one can subdue the world, even if it is as a picture. By now, everyone in this world is aware of the limitations of this activity – and this is precisely where the romanticism of Herbert Böttcher’s pictures comes in. By celebrating the great triumphs of technology for the last time, but by making these triumphs visible through small breaks in each individual picture, as in the sequence of this book, they lead all those who can both still marvel at the stupendous quality and take the trouble to look more closely, exactly where every good romanticism leads: to the understanding of the integration of human activity into the forces of nature. Much of this is also shown in these pictures, and every viewer can find this for himself in them, beyond all language.

Rolf Sachsse

The essay by Dr. Rolf Sachsse appeared in 2008 in the illustrated book Seamotion.